Is it too late to reanimate the ghosts of Pulitzer, Hearst, Bennett and Kane

to save the contemporary newspaper from yuppie self-infatuation

and terminal boredom?

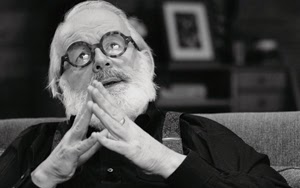

By Van Gordon Sauter

Former president of CBS NewsA well-intentioned colleague suggested I discuss the changes that will occur in the communications business over the next 20 years — by 2018. An engaging concept, until I thought back to what I might have prophesied in 1978 about changes in the industry by 1998. That was sobering.

Who in 1978, for instance, would have predicted that a rambunctious, hokey, idiot savant from Georgia…who inherited a bunch of billboards in snake- infested underbrush, along with an obscure Atlanta television station…would create a consequential force in world journalism…through CNN in particular, and cable in general.

Who would have anticipated back in the ’70s that a Seattle twit, a college dropout, would create the first commercial nation-state, known as Microsoft, or that incredibly well-financed entrepreneurs and dreamers at the other end of this state would daily be planning technological innovations to further overturn the world of communications that has served so many of us so well.

Or that a relatively obscure Australian press lord, who owned some flamboyant tabloids in San Antonio and New York City, would create a brilliantly interlocked media empire that spans the globe while staying at the cultural and technological cusp, conveying words and pictures to villages in India, Beverly Hills 90210, Sloane Street and the Internet itself.

Given all that, making detailed predictions about 2018 would be preposterous. So let me veer off in another direction and begin with — of all things — Edna St. Vincent Millay. She wrote some decades ago that “upon this gifted age…in its dark hour…falls from the sky a meteoric shower of facts. They lie uncollected, uncombined, wisdom enough to leech us of our ills if daily spun — but there exists no loom to weave it into a fabric.”

I suggest to you that such a loom currently exists, in the form of an information delivery system that has evolved through the chaos and brilliance of our free enterprise system. It is seven-tiered:

First, radio, with its directness and immediacy; then television, with its cinematic revelation; then, daily newspapers, with detail and background; then the weekly magazines, rich in context and remarkably well-written; then the monthly magazines, with the perceptions afforded by widely spaced deadlines; then the books, with the documentation and perspectives that initiate the process of historical perspective; and finally, the wild card, the Internet, spewing out voluminous amounts of chaotic, sometimes dubious but frequently valuable information.

If information consumers used that loom efficiently, extracting the correct strength from each tier, we would constitute a remarkably well-informed society. But we don’t.

I would like to speak to the newspaper tier of that loom, and the remarkable pressures it is experiencing…to the degree there are legitimate concerns as to whether contemporary managements, operation practices and editorial staffs can carry it into the technologically driven future. Let me speak to three pressing challenges: one, journalism’s rapidly escalating credibility gap; two, the onrushing competitive technology; and finally, the emotionally barren banality of American newspapers.

First, credibility.

At this stage, most American still believe journalists and writers are servicing this loom with accurate, fair and balanced information. But there is impending peril. Credibility is showing distinct erosion.

In my opinion, the blatantly liberal, politically correct orientation of the news media on social issues is leading many consumers to conclude that journalists have a private agenda. I am not speaking here to political issues, but to social issues, which are the true grammar of societal experience.

Furthermore, the vulgar proliferation of supercilious, argumentative print journalists on television has further undermined the image of objectivity, of journalism committed to fairness and balance. It doesn’t matter if these people are reporters or columnists.

These slick, facile, upwardly mobile media luminaries contribute to the growing perception that journalists are on the same team, joined at the hip, with the dreaded politicians, and thus the disdain appropriately directed at the Federal political caste splatters across journalism.

The severity of this credibility attrition is best measured by research revealing that even now…after years of wretched excess…local television news tends to have more credibility than national news, print or broadcast, and, in many cases, local print news.

Outrage at journalists is hardly new. Samuel Johnson described news writers as individuals totally devoid of talent or ambition. John Quincy Adams said they sit at street corners with loaded blunderbusses, prepared to fire them off for sport or hire at any selected individual. And Ben Hecht and Charles McArthur talked of journalists as individuals primarily occupied with peeping through keyholes, chasing after fire engines like crazed coach dogs or waking people in the middle of the night to ask what they thought of Mussolini.

And things have certainly changed since the era of Hecht and McArthur. Journalism has gone upscale. We have gone from beer and sausage to quiche and Chardonnay. Reporters are middle- and upper-middle-class. They are college-educated. They tend to have far different social and political perceptions that the public theoretically being served.

Beyond giving evidence of a true empathy for what closeted liberals now call a progressive agenda, a striking number of young journalists openly disavow, when they can pull it off, the traditional goals of fairness and balance in the editorial product. They are proselytizers for their own personal “take” on events. And editors so frequently seem collaborative, or — at best — disinclined or incapable of doing anything about it.

Personally, I think publishers and editors should demand adherence to the standard drawn from Cicero’s exhortation to the historians. The date was 80 BC, but its importance is undiminished by the intervening years. If you substitute the word “journalist” for “historian,” it reads like this:

“The first law is that the journalist shall never dare to set down that which is false. The second, that he shall never dare to conceal the truth. The third, that there shall be no suspicion in his work of either favoritism or malice.”

That is a fine aspiration for the journalist and an excellent test for consumers to use in judging the core integrity of their news product.

But to further complicate journalism, there are cascading new technologies. I am hardly a technology zealot. In regards to television technology, I know only that turning the knob to the right makes it louder. But I fear the print and broadcast companies have dramatically underestimated the impact of technological innovation. Over the next several years the Internet will begin to unravel some of the tiers in that traditional loom.

Doubters unfailingly evaluate future technology in the context of the current newspaper audience. But that current audience will be gone in the not too distant future. And the upcoming audience will be far, far more receptive to the upcoming innovation. They will have grown to maturity with it.

Evolving information, breaking news, even stored knowledge, are for a growing number of consumers mere commodities. Readily available, anywhere. It is remarkably easy for startup (companies) to obtain raw news and information and to hire people who can refashion and package it. The proliferation of ill- advised journalism schools punch-press our theoretically credentialed journalists in tragically redundant numbers. They generally tend to be mediocre in terms of skills and knowledge, but not much is actually required of them.

Newspapers frequently contend their destiny is assured because the product is comprehensive, accessible, cheap, portable and disposable. But I think they make a generational/institutional error in overlooking a computer monitor’s ability to integrate video and text, at the discretion of the screen owner. The personalization and immediacy will be breathtaking. And when that modem- driven monitor becomes portable, like a notebook, the newspaper as a physical, hand-held entity will not be able to compete with its range of content.

The decamping of Knight Ridder management from Miami to the Silicon Valley is highly symbolic. Even non-competitive newspapers are hard to manage. Managing the future is precarious, because we don’t know when and in what form it will arrive. But one thing is certain: The newspaper that puts all its chips on the printing press and distribution trucks is in grave jeopardy. The future of the newspaper — and video, for that matter — is daily evolving in the (Silicon) Valley.

But journalism has yet another problem that compounds the first two: content. For want of a better term, it is the problem of conspicuous obtuseness. And that is unforgivable, for it repudiates the heritage of this business.

Journalism has a history that refuses to surrender, to quietly retire from our memories. Each of us, raised on newspapers, has our museum of buildings and pictures and editors and colleagues and yellowed clippings and brazen woodcuts that conjure up in crystal-clear images the greatness of this business. They grip our imagination with unyielding tenacity.

Just a few generations ago, this industry’s savants and romanticist, saints and rotters, strode across the rambunctious stage of America, fashioning a passionate industry, if not a robust nation, while holding a fiery contempt for those who preferred or cowered in the protective offstage darkness.

But today, our stage seems tediously fastidious, brittle and abstemious, insufferably proper. Those who cowered offstage now seem to own center stage. They are running the damned things. Their products are exhaustingly safe. They rarely, if ever, risk offense. Or take risk. Or call a scalawag a scalawag.

It wasn’t long ago that communities were so conscious of newspapers that they seriously discussed the merits of tarring and feathering editors and riding them out of town on rails. Who would even notice today? Is there anything in papers today that would lead you to have a sense of the editor? If Oscar Wilde was correct when he said dullness is the coming of age of seriousness, then our anonymous editors have elevated seriousness to a suffocating dullness.

I used to declare in speeches that journalism has advanced dramatically since the days of the knight-errant publishers and editors. I no longer believe that. Those scoundrels gave us reasons to read. To buy papers. They engaged us, causing us to screech with fury at their latest excess or to cheer another bombastic crusade of critical importance. There was a zest to their endeavors.

I fear that in a majority of communities readers sense an almost total absence of outrage or energy or enthusiasm in behalf of their core concerns — the concerns of the community. One senses today that the journalists, particularly print journalists, represent the special pleaders, if they represent anyone at all. In too many cases pages are lifeless. Writing is banal. Columnists don’t kick butt. There is an apparent abhorrence of flair.

We need some reincarnations of Pulitzer or Bennett or Hearst. Or Citizen Kane, for that matter. Tits, tots, pets and vets is the editorial formula allegedly dictated once by The Chief. Why not some contemporary, more studied version of that? Why not editors and news directors and publishers who love aggressively pugnacious and passionate editorial crusades?

Why can’t we have editors:

- who manifest unrelenting outrage at our inexcusable political class;

- who rail against the administrators and educators of schools that obviously fail our children;

- who cry out in sympathy when they see willing workers unable to find jobs or educations that opens up new careers;

- who fire employees when they become self-aggrandizing television stars or best friends of politicians or obsequious golf partners of greedy executives;

- And what about term limits for beat reporters? What about diversity — social perception diversity — as another mandate for the newsrooms?

- And while they are at it, why not editors who fire all those toady employees who attend gridiron dinners or correspondent dinners? Does any reputable journalist ever want to attend another White House Correspondents dinner, where every table now must have a floral arrangement and a Hollywood starlet with a low-cut gown?

Over the past few years, as I tumble and stumble toward codgerhood, my news consumption is decreasing rather than increasing. The Internet gives me the news service wires, columnists, local headlines, gossip pages, front pages, weather and sports. I check it three or four times a day. I unfailingly read my home-delivered New York Times and Wall Street Journal at the top of the day. Most days, I read a local paper. But it isn’t really, to me, a local paper — though I think Willes and his group will make the LA Times a much better newspaper. It covers a vast metropolitan area. In 25 years, it will add the equivalent of two Chicagos.

But the area I live and trade and move about in — the area that I call home — has a population of about 300,000 people. In the next several years, an Internet news service will begin to daily cover this community. But at this stage, the LA Times, out of necessity, covers Pasadena far more than my unrecognized community. But I go to New York or Chicago or Ketchum, Idaho — my God, I go to Paris — more often than I go to Pasadena. So missing a day or so of the so-called local paper is never perceived as a loss. It is rare to buy a newsmagazine for its news. Local or network news is watched only where they are bound to contain some video of compelling interest.

In terms of content, I no longer read stories about Near East peace talks, dissent in China, AIDS, Bosnia, Africa, feminism, the so-called balanced budget, gay political aspirations and many other inexplicable editorial fixations.

In so many of those categories, the daily stories represent only the most superficial, incremental changes. I again started reading Northern Ireland stories about six weeks ago, and discovered that I missed nothing in the years of stories I ignored. All this while, the newsroom dedicates incredible amounts of energy to social issues that are more reflective of newsroom agendas than the needs or curiosities of the society.

We are in a declining journalism that has fed and occupied many of us for the last several decades. It is limping off into inconsequence.

It is not yet clear what precisely will take its place. Or when. But I suspect technology will force improvement at both ends of the journalistic bell curve. Upscale information sources and tawdry information sources will grow in accessibility and effectiveness. And the pace of change will be more rapid that we ever imagined.

A little more than 50 years ago, one of the visionaries declared there would be a world market for no more than five computers a year. That came from Thomas Watson, a champion and guiding inspiration of IBM. And a few years later, Popular Mechanics, operating from a similar mind set, looked deep into the future and joyfully predicted that individual computers would ultimately weigh no more than one and a half tons.

In “A Farewell to Arms,” Hemingway speaks of a great fallacy: the wisdom of old men. Old men do not grow wise, Hemingway declared; they just grow careful. There is much in life about which we must be quite careful: our honor, our relationships, our commitment to truth. But we can’t give automatic defense to the crippling caution of old men. We must walk through new doors.

In one of his master fictions, Graham Greene wrote that “there is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” Personally, I am not convinced that the door opens in childhood. I think it comes later. Sometimes much later. And it opens a lot. But when the door to the future opens, there is a deceptive absence of fanfare, no assemblage of trumpets heralding a great epiphany, a startling revelation. Our vulnerability is that one can pass through the door to the future and not recognize it — not realize the transition, let alone the new vistas and opportunities.

To recognize the open doors in journalism will require a swifter management than we have seen to date.

And in the best of all worlds, the ombudsmen should play a far broader critical role — beyond addressing the curiosities or inherent frustrations of the readers.

The ombudsmen — the degree that it is feasible — should be blunt and forceful advocates for jounalism that is relevant and passionate and filled with elan.

Ombudsmen should demand not just accurate and fair coverage, good taste and impeccable motives — but damned better newspapers. Ombudsmen should be agents of change. Tricky? You bet. But as television becomes more silly and indulgent, as the new technology siphons off consumers, newspapers can best respond and compete by, of all things, getting better.

And you — removed from the day-to-day anguish of manufacturing newspapers — should be empowered to publicly evaluate the paper’s performance. Its commitments. Its passion. If the newspaper is not moving to make schools better, for instance, your column should inquire why not. And if the paper is indeed working to enhance the schools, you should be capable of celebrating that performance.

While always centered on the newspaper, the ombudsman should be a media critic — to also see the newspaper in the context of that loom, that far wider editorial mix to which all readers are subjected, whether they like it or not.

In the consumption of news and information, people don’t compartmentalize the sources. In reality, everything gets jumbled together. It is probably a disservice to totally isolate the newspaper from the broad media mix. There are occasions when you should look beyond the paper alone to evaluate how all the news sources are performing.

Readers need more from you. Your writ must be expanded. Your venue more far- reaching. Your voice spread across a wider range of issues. We need editors bold enough to push envelopes, and also bold enough to empower the ombudsmen in their public role. We need editors who make ombudsmen make him or her sweat for a living — to get pushed out on limbs to give him or her full employment. I wish you Godspeed.

A native of Ohio, Van Gordon Sauter graduated from Ohio University in 1957. He entered the advertising world but resigned as an assistant producer of television commericals to pursue a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri.

After working for a daily paper in New Bedford, Massachusetts, he joined the Detroit Free Press and covered civil rights and urban affairs. Later he joined the Chicago Daily News, covering a wide range of stories, including the urban riots in Newark, Detroit and Chicago.

In 1968 Sauter joined CBS and over 18 years held a variety of jobs including on-air commentator and news director for WBBM News Radio in Chicago, and executive producer, CBS News Radio in New York. He was Paris bureau chief for CBS News, and vice president for program practices for CBS Television. Later he became president of CBS Sports and president of CBS News. He resigned from CBS in 1986.

Until recently Sauter spent two years as president and general manager of KVIE, the public television station in Sacramento, Calif. He resides in Los Angeles and Ketchum, Idaho, and is married to Kathleen Brown, an executive vice president of Bank of America and former state treasurer of California.

A native of Ohio, Van Gordon Sauter graduated from Ohio University in 1957. He entered the advertising world but resigned as an assistant producer of television commericals to pursue a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri.

After working for a daily paper in New Bedford, Massachusetts, he joined the Detroit Free Press and covered civil rights and urban affairs. Later he joined the Chicago Daily News, covering a wide range of stories, including the urban riots in Newark, Detroit and Chicago.

In 1968 Sauter joined CBS and over 18 years held a variety of jobs including on-air commentator and news director for WBBM News Radio in Chicago, and executive producer, CBS News Radio in New York. He was Paris bureau chief for CBS News, and vice president for program practices for CBS Television. Later he became president of CBS Sports and president of CBS News. He resigned from CBS in 1986.

Until recently Sauter spent two years as president and general manager of KVIE, the public television station in Sacramento, Calif. He resides in Los Angeles and Ketchum, Idaho, and is married to Kathleen Brown, an executive vice president of Bank of America and former state treasurer of California.

Time in Tunis

Time in Tunis